The day I received a copy of a book I had ordered on the history of cycling in the dutch capital city, Bike City Amsterdam, I also happened to read a very brief summation of that story by London-based journalist, Dave Hill, in his On London blog. Hill is a frequent critic of physically separated cycle lanes which form an important part of Amsterdam’s renowned cycle network. He comments that Amsterdam’s cycle network ‘emerged from a long period of quarrels and compromises in which lanes were installed to discipline cyclists rather than to liberate them’ (https://www.onlondon.co.uk/dave-hill-will-the-pandemic-produce-a-london-cycling-golden-age/).

This rather surprised me as I’d not come across such sentiment previously as a motivation behind the development of an admirable bike network in the Netherlands in general and Amsterdam in particular. So the arrival of Bike City Amsterdam, by Fred Feddes (in collaboration with Marjolein de Lange) was a serendipitous coincidence. The book is subtitled How Amsterdam became the Cycling Capital of the World and chronicles the social and political forces the came together to create Europe’s best known cycling city. However, distinctly absent from Feddes’s account is any suggestion that the city got its network to discipline cyclists, rather than as the work of activists and others who sought to make cycling safe and attractive and to establish cycling as an essential means of transport in the modern urban environment.

I tweeted Dave Hill asking him if he could share details of the source(s) of his assertion. Not getting a reply, I’ve now tweeted him two further times, but again with no response. I leave the invitation to respond open, so Dave, if you are reading this, please feel free to use the comments option to reveal your source(s) and add to the richness of our understanding of how cities adopt pro-cycling policies.

It’s easy for foreigners to view cycling in the Netherlands as something that is done by everyone and to imagine that the entire population are avid cyclists. But, as Hill correctly points out, cycling in the Netherlands, as elsewhere, is a contested activity and many aspects of cycle policy have been and still are being quarrelled over in the self-proclaimed ‘cycling capital of the world’. One interesting chapter in Bike City Amsterdam recounts the bitter ten-year struggle to preserve a cycle passageway under the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Some of those who wanted to scrap or divert the cycle route used such terms as ‘bicycle terrorism’ and ‘bicycle fundamentalism’ to describe supporters of retaining the cycle route in opposition to the desires of the museum management to divert it. These are terms we in the UK are used to hearing from London’s cab drivers and anti-cycling councillors, but don’t really expect to hear used across the North Sea.

The Amsterdam motor lobby has fought hard over the years to resist the advances made by bicycle campaigners and it must be acknowledged criticisms are indeed voiced about unruly cyclists. Despite that, foreign visitors to Amsterdam cannot fail to notice the prevalence of the bicycle on the city’s streets (and in other Dutch towns and cities too). Foreign bicycle activists are especially impressed and jealous of the seemingly ubiquitous and high-quality of bicycle infrastructure.

Bike City Amsterdam certainly contains a lot of material that will be of interest to what British cycle campaigners call ‘kerb nerds’ – activists who develop a deep knowledge of the technicalities of cycle track design and the like. However, I hardly mention this sort of matter in this review of the book, hoping instead to convey something of the historical dynamics of social change recounted in its pages.

It’s all too easy to say, as many have done – even including some leading cycle campaigners – that Amsterdam has its bike network because cycling is deep in the Dutch culture. This, of course, is intended to imply that it will be impossible to replicate cycle networks in countries which lack that culture and that we should not bother to try. So it is important to get a valid assessment of how Amsterdam became such an iconic cycle city.

Feddes describes how Amsterdam got its bike network, not from an inherent cycling culture, but due to a convergence of various social and political forces. As he writes, ‘Amsterdam could have ended up looking like car-dominated cities such as London, Paris, Madrid or Hamburg, where some space could only be created [for bicycles] later with a lot of effort … but in the end a different course was taken. There was no single cause for this reversal; instead it was the outcome of a confluence of some fortunate, semi-accidental and semi-deliberate factors.’

About the nearest that I came to finding anything in the book to substantiate Hill’s assertion about disciplining cyclists dates from the 1930s. A city transport planner is cited as saying that ‘The bicycle is an ideal means of transport for its rider. The tractability and small size of this vehicle, however, enable the cyclist to use it in all kinds of “individualistic manners” that make this means of transport extremely unruly and unmanageable for the experts.’

By the 1950 and 1960s, national Dutch transport policy aimed to facilitate the growth of the motor car as the key means of personal transport. Cycling was seen as an old-fashioned, outdated means of transport that was set to disappear from the streets. The British Buchanan report was a major influence on Dutch planners. Buchanan is cited observing that, ‘for obvious reasons of safety and the free flow of vehicular traffic’ it made sense to keep bicycles away from motor vehicles – but he opposed the means of doing so. ‘It would,’ he said, ‘ be very expensive, and probably impracticable, to build a completely separate system of tracks for cyclists.’

In the 1950s Dutch town planners often wanted to demolish existing city and town centres to make space for the expressways necessitated to cater for motor vehicle traffic, and without room for the bicycle. Plans were presented that would have driven highways through the middle of Amsterdam, requiring the demolition of swathes of the historic city centre. Feddes even observes that, ‘Occasionally one can note some sense of jealousy of bombed-out cities like Rotterdam, which had much more flexibility in terms of modern traffic planning.’ In some cities, such as the Hague, canals were filled in to be converted into roads.

However, such proposals roused opposition from those wanted to preserve the beauty of Dutch towns and cities. Here was the first sign of resistance, indirectly, to the forward march of the car.

As well as new roads, policy also discouraged cycling. ‘The repression suffered by the bicycle was visible everywhere’, says Feddes. ‘In 1960 [Amsterdam] City Council ruled that the narrow Leidsestraat had become too busy to allow unrestricted access to all types of traffic, namely trams, cars, bicycles and pedestrians.’ Their conclusion was to ban bikes. ‘Policy makers, urban planners, traffic engineers and futurologists announced that cycling as a form of transport was dead … many forward-thinking experts were secretly happy that the bike was on its way out, because it was seen as part of the problem and not as a possible solution.’

Feddes quotes one view that ‘a city with excellent public transport will not have to contend with such chaotic street situations [i.e. the presence of bicycles on the streets].’

Dutch journalist Ben Kroon wrote in the 1960s that ‘Until recently the cyclist has had absolutely no status in either traffic or society in general. The Traffic Act treats them like a bothersome fly. … The cyclist was still the pariah of urban traffic and, in anticipation of its inevitable extinction, we had to struggle for survival day in, day out.’ As yet, however, there was no organised resistance to the planned demise of the bicycle.

By the early 1970s a sort of stalemate had been reached. Urban campaigners saw off attempts to demolish city centres, build flyovers or fill in canals. They aimed to protect the city’s heritage from rampant motorisation. ‘For the first time public opinion placed an unequivocal limit on the power of the car to dictate urban development … That in itself did not automatically lead to a bicycle city, but when traffic tensions escalated in the 1960s and 1970s, the hidden benefits of the bicycle were rediscovered.’

Yet the number of cars on the streets grew apace, crowding the city streets, requiring new, wider roads to drive along and vast areas given over for parking – and all the while exacting a tragic toll of lives lost and fragile flesh and bone crushed in collisions. In 1965 Amsterdam experienced 31,868 traffic accidents with 93 deaths and 5,655 injured. Numbers of victims of the motor vehicle rose relentlessly. Nationally in the Netherlands there were 3,264 fatalities in 1972, 457 of whom were younger than 15 years of age. This was taken as something normal. Little fuss was made about the carnage.

But social changes were also taking place. The city’s social structure was altering, with growing numbers of young adults moving to Amsterdam to study, to get a good job – and to enjoy city life (there is a saying in Dutch: Rotterdam verdient het, Den Haag beheerst het, Amsterdam viert het – Rotterdam earns it, the Hague governs it, Amsterdam parties on it). The incomers moved into the cramped nineteenth century districts, some of whose residents had cycled to work in the docks and factories, but were now encouraged to migrate to newly developed and more spacious suburbs and then often had to drive to work. But many chose not to move and continued to cycle in the city, while others bought cars and clogged the streets. The incomers had cycled as kids in the small towns and villages, and brought their bicycle with them to the big city and found it to be the perfect way to move around the city.

At the same time, social movements such as the ‘Provos’ in the mid-1960s and other activists in the 1970s began to agitate for a better quality of life in the city. Residents in crowded inner city districts began to agitate for ‘play streets’ and to ‘Stop de Kindermoord’ (Stop the Child Killing).

Over time cycle activism grew in extent and sophistication. On 17 February 1970 twenty-four cargo bikes ‘squeezed their way through rush-hour traffic’ in Amsterdam. ‘Police ordered the riders of these cargo bikes to leave because they were obstructing the traffic. The cyclists refused, claiming that ‘We are commuting to work on our cargo bikes.’ In March another action took place with 50 cargo bikes. And a third was organised in April. As Feddes observes, ‘ The logic annoyed motorists and authorities, but it was hard to refute: how can we be hindering traffic as we are traffic.’ In May and June demonstrations took place with wrecked cars used to block streets. The first call for a bicycle demonstration for a ‘car-free’ city was issued in May 1974. In 1976 a demo attracted 4,000; in 1977 it drew 9,000 and in 1978 a massive 15,000.

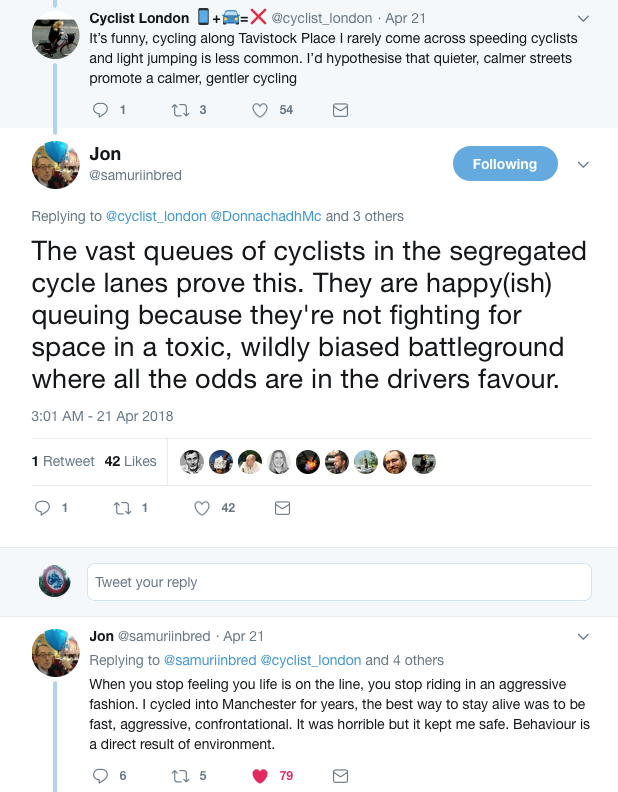

Activists also developed expertise in what was needed to make cycling a practical possibility in the age of the motor car. As Feddes observes, ‘Before the car took over, the street layout was simple and clear … The car, when it arrived, occupied much of the space in the street, and introduced stark differences in hardness, speed and vulnerability. The minimalist road design of old turned into a free-for-all where survival of he fittest was the only rule. Making the street suitable again for every road user required a thorough redesign. This was no minor task. The car had rapidly acquired a customary right to public space, which was vigorously defended by both business people and the growing number of ordinary car-owners in Amsterdam.’

Proposals were lodged with the City Council to treat the bicycle as a ‘full-fledged alternative in public transport.’ The transport brief in the city had traditionally been given to the PvdA (Labour Party) and its appointees had favoured policies leading to the ‘democratisation’ of the car and the building of suburbs requiring the use of the car. But some planners officials and politicians began to question the wisdom of rampant pro-car policies. The key development came in 1978 when PvdA aldermen were appointed to planning and transport posts who were committed to changing the priority given to the motor vehicle in the city. With this change of political policy-making, ‘The powerful Public Works Department suddenly became a bastion of outdated expertise, overtaken by new concepts and different forms of developing skills and knowledge.’

The PvdA began to embrace a pro-social policy favouring the less powerful – women (the majority of cyclists), children and the elderly. According to the ‘Bicycle Memorandum’, defending the interests of the bicycle was not for the sake of a minority, it was for the common good.’

However, ‘Reaching the heart of power did not mean that cyclists had already won the battle … They remained a vulnerable party in the conflict being fought out there. Nevertheless, the defence of the bicycle had shifted from the radical margins to the political centre.’

So the key point is the convergence of these various social and political forces: cycle activism (who agitated for change and provided technical expertise te professionals lacked); resident campaigns for safety and environmental improvement; city preservation lobbying; and modernisation of social policies in political parties. There was obviously some joint participation by individuals in more than one of these social currents, but they grew initially somewhat independently.

Plans were developed for a comprehensive cycle network. Car traffic in residential neighbourhoods was to be limited by concentrating through traffic onto main roads. ‘Tackling the parked car proved to be the best starting point.’ However, reducing car ownership was never really treated as an essential policy. The motor lobby campaigned against promotion of cycle space under the slogan, ‘Blij dat ik rij’ (Happy that I drive).

Over the next few decades, as more and more cycle-friendly infrastructure was introduced, cycling levels grew and, from the mid-1990s, car travel declined. In 1986-91 the average number of bike trips in the city on a working day was 470,000; in 2000 that number had reached 600,000 and by 2015 it topped 710,000.

The success of the bicycle network has now even begun to create its own problems as capacity of bike lanes proves to be inadequate. New, and often faster, forms of vehicle, such as the fast ‘snorfiets’ (a motorised form of bike/moped) and small cars were legally permitted to use bike lanes. And the spatial dominance of the car was in many respects still in place. In the 2010s of the 45 hectares of space available for transport in Amsterdam 25 percent was devoted to bike lanes, 4 percent to tramways, 20 percent to motors on the move, and a massive 60 percent to parked cars.

In another book, Het Recht van de Snelste (the Right of the Fastest), by T Verkade and M te Brömmelstroet, it is noted that the space allocated to car parking in the whole of the Netherlands is equivalent to the entire area of Amsterdam. 92 percent of that total national parking space is on publicly owned land, mainly ‘on street’. In Amsterdam the market price of a parking place would be Euros 3,600, but the actual cost of an annual city centre parking permit is Euros 535; in Rotterdam it is Euros 69. The data was compiled by the economics writer of De Correspondent, J Frederik, who wrote ‘We must make parking much more expensive … [it would be] the solution to almost everything.’ The book lays out how ‘fast traffic’ still holds a tight grip on national policy-making, something that Bike City Amsterdam only hints at.

The absence of a strategy for reducing car ownership is perhaps the major weakness of Dutch transport policy.

Despite that, nowadays the cycle networks of Amsterdam and other cities, such as Utrecht, are the envy of cycle activists and modern city planners all round the world (as is evident from my twitter timeline with links to campaigners in Europe, Africa, the Americas and Asia).

Even as we in the UK think about how we can strive to catch up with Dutch ideas on cycling and the city, the Dutch themselves are looking ahead to where they should be heading. Even Amsterdam faces challenges, as outlined in the book. Among those challenges is an ageing population. Feddes says, Dutch cycle policy now needs to be aimed at making cycling more inclusive. ‘A bicycle city that manages to incorporate an ageing population may well be Amsterdam’s contribution’ to the global challenge of sustainable and equitable mobility. ‘This places specific demands on traffic control and road design, and more generally on the calmness and clearness of traffic … Bicycle friendliness for children and for the elderly is the ultimate benchmark for the liveable and healthy city.’

I recommend Bike City Amsterdam as an essential handbook for how bicycle policy can become effective. It remains necessary to distinguish between specific Dutch/Amsterdam factors and ones that have general applicability, but there is much to learn here from a largely successful political policy-making process. In view of the urgent climate crisis, Amsterdam’s success with cycling is a lesson we all need to learn.

I have drawn out only a fraction of what can be found in this richly packed (and superbly translated) book and Bike City Amsterdam is as good as starting point as you are likely to find for advocates of treating cycling as a fully legitimate form of urban transport. Buy it, read it, learn from it, act upon it.

My thanks to Ken Wynn @highfielder80 for permission to use his photos of the present day cycle network in Amsterdam.